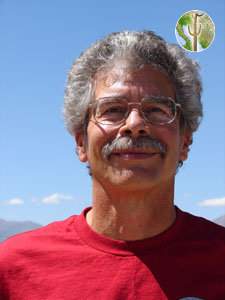

Tim Lengerich, we miss you

Tim was a man who cared deeply for this region - the Sky Islands and especially the Sonoran Desert. He harassed the Forest Service consistently, worked hard to restore damaged landscapes, and wrote songs about all the beauty in the region. Hear some of his music here.

Tim was a man who cared deeply for this region - the Sky Islands and especially the Sonoran Desert. He harassed the Forest Service consistently, worked hard to restore damaged landscapes, and wrote songs about all the beauty in the region. Hear some of his music here.

He spent countless hours camping and hiking wild places many of us never see. More than anything he hated seeing the places he loved destroyed, no matter by what hand. For this reason he really, really hated cows and ranching and tirelessly tried to stop it and teach people about its destructive impacts.

Tim had a heart attack and died on a summer day in 2010. He was hiking alone in Cabeza Prieta, pretty much his favorite spots on the planet. See his last set of photos from that day on Facebook.

We will always miss you, Tim. Hozho.

Here is a story that Tim wrote not long before he died of a hike he took in the Baboquivaris. He describes himself having what he thought was dehydration during the hike, but what was almost certainly an earlier heart attack. Still mentally and physically strong Tim worked through it pushing himself to finish.

The goal: hike to the top of Baboquivari Peak (7734') of the Baboquivari mountain range sixty miles southwest of Tucson, near the Mexico border. This volcanic plug juts impressively into the sky; a stark, steely-gray stub.

The 8 a.m. start turned ugly quickly. From the kiosk parking lot in Brown Canyon, I began on what I thought was the trail. It wasn't. I tried another likely path. It wasn't either. It turns out there is no trail, merely access.

So I walked down and around the locked gate across the road that runs to the only local residence, then to the Brown Canyon Environmental Education building farther up.

Near the house, about a half-mile in, I kicked up a turkey. I quickly grabbed at my waist for my camera, got air instead. It was gone. I reflected back to an especially hard tug at my beltline while busting through some catclaw on one of the faux trails noted above. It had to be there. Back I went.

I searched to no avail, and finally decided to resume the hike without it. I was greatly disappointed, and noted how much my ego was tied to my photography—putting pics on the internet, sharing them with others, etc. I felt a little foolish about that and decided it was a good exercise in humility to proceed sans camera. Back to the road. An hour lost.

In less than a mile, I began to notice that my shoulders ached and my legs felt a little weak already. Something unusual was going on. I was still on flat terrain and the temperature had likely not yet reached ninety. What was wrong? With the earlier false starts, the loss of the camera (and time), and now this, things began to augur for aborting the hike until the next day. The first ominous portents of the day to come? Should have read my coffee grounds. It is said that if they take on the shape of shoes, you will have a long way to travel before you are happy.

But these thoughts passed, as I had faith in my mental and physical strength, endurance, and in the likelihood that the aches and weakness would subside. Onward.

I had packed about five and a half quarts of water and decided to leave fifty ounces in a cache for my return about 1.5 miles in at the unoccupied Environmental Education building. Big mistake. Idiot.

By 1:30, I was over three miles in, high up the canyon flank, down to two quarts of water, and Baboquivari Peak was out of sight behind a ridge. I ate two handfuls of raisins, nuts and seeds. My first food of the hike, and last.

A ridiculously belated check of my GPS unit showed well over a mile to go in a different direction than I had been hiking. But I was now locked into steep, uncompromising terrain, too tired and too late to alter course.

My physical condition had deteriorated quickly. Breath and pulse had turned rapid and I could not recover them. I climbed only ten to twenty feet at a time before collapsing, trying to catch my breath. For the rest of the day I never did. Classic dehydration symptoms. Yet I deluded myself into believing I could make it. Onward. Idiot.

For the next hour, I continued the oblique course I was locked into, water supply dwindling, mental and physical fatigue well set in, and 1.15 miles to go. Then finally the ridgeline, and the ragged route to Baboquivari Peak appeared. Hope sprang. While the temperature climbed higher, I ran out of water, was huffing horribly, uncontrollably, and had one half-mile more of harsh hiking, just to get to the base of the plug. Having climbed this mountain in the nineties, I knew that I was still in for hard work upon arrival. While faith in myself remained strong, I should have turned back long before. Unbelievable foolishness.

Then I stumbled upon a mountain seep. I was quite excited until I discovered there was no accumulation of water and that I wouldn't get any from the moist moss growing down the rock. Still, I fumbled around in my first aid kit and found a small vial that held little more than a tablespoon. I placed it up to the rock face wishing water into it, to no avail. Where was Moses and his rock-knocking, water-producing staff when I needed him?v I finally neared the base of Baboquivari and struck upon a trail leading farther up and, possibly, to my goal. But it dead-ended into a high, overhanging crack in the rock, and further frustration.

There, incredibly, I found another seep with a small puddle of water as big around as a fist and a half-inch deep. I dug out the vial, scraped the pool a little deeper and drank about fifty vials of water, a tablespoon at a time. Laughable and ludicrous, but my spirits soared and I said to myself, "You can do this, Tim." Idiot.

Off I set seeking a different route. From that nineties trip, I seemed to remember ascending from the southeast side so I began to hike down a ways to curve around to the west and south.

Early into this latest delusion, I stepped off a short ledge and plopped my left foot down next to a Black-tailed rattlesnake. Needless to say, we were both shaking like a puppy poopin' a peach pit 'til I could lurch myself back up out of harm's way. Amazing luck not to have suffered a bite that, with my terribly compromised condition and remote location, could quite possibly have killed me. Lucky idiot. Onward.

(As a former Catholic, steeped in the ways and characteristics of the saints, I still begin most hikes beseeching the guidance of St. Anthony for a safe return, and the blessing of St. Francis of Assisi for exciting animal encounters. Half of that investment was now fulfilled.)

Later, after expending far too much energy, I realized my current course wasn't the way. Any southeasterly route I had used years ago must have originated higher up the plug from some point I could not now find. I sat down to regain my breath (fruitlessly) and to think (for a change). Thus far, I had been guided by dogged determination instead of intelligence. I finally embraced the thought I should have grasped with a stranglehold miles, hours, and quarts of water before—get thee back to the truck. It was now 5 p.m., four miles and two drainages away from camp, out of water and food, and more exhausted than I had ever been. Sixty years of age is no time for a landmark experience like this. Only one thing for it. Downward. Idiot.

Later, after expending far too much energy, I realized my current course wasn't the way. Any southeasterly route I had used years ago must have originated higher up the plug from some point I could not now find. I sat down to regain my breath (fruitlessly) and to think (for a change). Thus far, I had been guided by dogged determination instead of intelligence. I finally embraced the thought I should have grasped with a stranglehold miles, hours, and quarts of water before—get thee back to the truck. It was now 5 p.m., four miles and two drainages away from camp, out of water and food, and more exhausted than I had ever been. Sixty years of age is no time for a landmark experience like this. Only one thing for it. Downward. Idiot.

I must attest, the morning's apprehension notwithstanding, I cannot believe my legs continued to serve. I was still stopping every twenty or thirty feet, trying in vain to catch my breath, but my legs never failed. Must be the yoga. At the first of two saddles I looked down its eastward drainage and realized for the first time that I had used the wrong canyon for my trek—Brown Canyon, instead of the correct Thomas Canyon. Poor preparation had nearly killed me and still might. Idiot.

By the time I reached the second saddle, dusk was approaching and I began to ponder the likely prospect of spending the night in the mountains. I had recently twice climbed down a mountain at night. Once in sunglasses. A cartoon! I was in no shape for another such venture.

For the first time that day I had the urge to urinate. For the first time in my life, I thought of drinking it. For the first time in my life, I did. I drained into an empty water container. While it was dark yellow and a little salty, the three-quarters cup I produced was not particularly repulsive tasting. It was my first "water" since the second seep for an accumulated total of about two cups after many hours of intense trudging in high heat. I would have been as well served by a rabbit's foot. The next spot I stopped to rest became my bed for the night. I lay down with my pack for a pillow and breathed heavily and rapidly for at least an hour. I couldn't believe it! Finally, in the next half-hour, I began to catch my breath and rest more easily. I barely moved until 4:30 a.m., when the sun seeped onto the horizon and I could read the time on my GPS unit. But for hours I lay unsleeping, with leg cramps and tingling in my left arm--all symptoms of dehydration. I asked myself did I have the energy to remove even one of the rocks poking into my back? Each decision, each adjustment was preceded by considerable deliberation.

Eventually I lapsed into sleep and dreamed of a gray wolf with a stiff, right rear leg hobbling away from me down a creek bed. Then it turned back as if to investigate me, and the dream faded. Around 5 a.m., I collected myself and began the final leg of my journey: two miles down canyon to the water cache and the road back to my truck.

By the precipitous nature of the drainage, I suspected that I would soon encounter "tinajas"--pools of water captured in the rock. I was not disappointed. I buried my yap in the first one and sucked with great satisfaction. For some reason, I could not take in a lot of water and a certain sense told me that was the way it should be. The next shallow pool was full of small tadpoles that had the fright of their short lives when my lips spread down into their liquid lair. In truth, they were doomed despite me. What little water there was would likely soon evaporate and they would be off to tadpole heaven, if not another animal's belly, a secondary route. Eventually, with great relief, I stumbled across a fat trail I knew led back to the education center. Still, I had little energy and walked the next mile as slowly as a prisoner to the gallows pole. I fished my fifty-ounce water cache out of the galvanized, lidded bucket I had stored it in on the back porch and began to drink slowly, happily. Sitting at a picnic table, I rested my forehead on my arm between drinks of water. With my journey nearly over, I could barely keep my head up and sat for nearly an hour recouping, 1.56 miles from camp. Eventually, I rose and slowly trundled to my truck. Arriving at 8:30 a.m., I stripped naked, grabbed food and water and slipped into my air-conditioned truck for two hours, dully reflecting on my journey; now, over twenty-four hours from my start time, sixteen with negligible water, most of it without food, under arduous, hot conditions of my own crazy making. No more onward. Still an idiot.

Some energy now returned, I dressed myself again in the filthy, stiff, sweat-dried, clothing I had left strewn about on the ground and set out to find my camera. With slow, careful coursing through the area in which I believed it to be, I found my camera on the ground waiting for me below some catclaw. Hallelujah!

Some energy now returned, I dressed myself again in the filthy, stiff, sweat-dried, clothing I had left strewn about on the ground and set out to find my camera. With slow, careful coursing through the area in which I believed it to be, I found my camera on the ground waiting for me below some catclaw. Hallelujah!

In one spin of the earth around the sun, I had lost my camera and ten pounds, found my camera, nearly killed myself, gained renewed awe for the incredible capacity of the human body, and experienced the equally incredible capacity of the mind to lead the body around like a pull-toy on a string!

Never before; never again. Maybe. Onward.