Twelve Days From the Rio Tutuaca

By Huck

Recently I had the opportunity to see, by raft, the country I've been tramping overland for the last couple of decades. Just getting to the put-in of our trip was a logistical conundrum and an exercise in patience. We needed a shuttle driver who was comfortable in the fringe area of Copper Canyon, Chihuahua, and the driver might have to spend two, maybe three nights on the road before getting home. Then he would have to pick us up in 10 or 11 or 12 days; and who knew for sure. This trip is best attempted when the water has a good flow, but unbeknownst to us, a tropical hurricane (Norbert) was heading for the sierras preparing to drop 3 days of solid rain in the drainages that fed our rivers. We recently had some decent enough flows from summer monsoons after a prolonged dry spell to even attempt this project. As it turned out, it rained all night and part of the second day as we headed deeper into Chihuahua from the take-out point near Sahuaripa, Sonora. The side canyons in the cordillera of the sierras were roaring with brown water--not a good sign. The next day we contemplated a delay, but a promising sucker hole of robin egg blue sky beckoned us further as we polished off breakfast of strong coffee, papaya and granola bars. We left the highway on a broad sinuous dirt road for the last 100 kilometers, a four hour drive to a rickety logging bridge halfway between Yepachic and Madera. (Photo gallery from trip)

Rio Tutuaca at the bridge was a torrent of angry brown water. It was flowing fast past the shallow access beach upstream from the bridge, but below the bridge the canyon took hold and huge boulders cleaved from the sheer cliffs above split the channel in some challenging ways. Lucky for me that the experienced rafters merely glanced at the bucking brown bronco and the innocuous strainers, and plotted their lines instead. In the hour or so that it took us to get going the river rose almost 6 inches and water started piling onto the bridge abutment. It looked like my first stroke with a borrowed boat and a borrowed paddle had better get me in the right position or it would all be over quickly. I was lucky, but gripped. I skirted the trees on my left as I aimed for the safe current. The water was flowing fast past the big boulders on my right and a wall below a pump station on my left, but then I couldn't maneuver fast enough through some smaller boulders and went through backwards. The current was carrying me along, and try as I might, I couldn't get turned downstream. Around another boulder backwards and we were into smooth fast water with time to get my breath. The inflatable kayak had performed flawlessly. The scenery was spectacular. The sheer fluted walls of the Tutuaca Narrows rose straight up about 200-300 feet. There was no bank, and the water was way up the tree trunks, and everywhere the rich green of parched plants responding to a plentiful rain was overpowering. There was no bank?

We got underway late in the day, but the last thing on my mind was camping. But IF we were going to camp, we would need a bank, and after a couple of hours of paddling there appeared a low overgrown bench that from where I sat looked like nothing more than a dense thicket with a few boulders at the base of a steep craggy cliff. This was camp and it was across the river from a beautiful little waterfall cascading serenely into the muddy river. Now it was time to see how all this preparation paid off. The brains behind this adventure were Neil and Lacey. They were in catarafts, as was another member of the expedition Steve, but his cataraft was a bit smaller. My friend John was with us in an IK (inflatable kayak). Neil and Lacey had made the trip before from a tributary that we would see in a couple of days. So for them the only thing new was a little stretch of river. Everything for my was new. One of the coolest things was that you could make seven kilometers per hour exerting hardly any energy, unless they decided to eddy out. Then I had to paddle like hell to get to a point where there was slack current. Usually I paddled too hard and overshot the mark, and got in the upstream eddy too soon, and ended up expended ten times the energy required for such a simple maneuver. Such was the case at our first camp. I barely had enough strength after beaching to offload my share of stuff. Food, kitchen pots and pans, cans, stove and fuel, more food, and a table. We really had remarkable little gear for a ten day trip. But we had tequila, and happy hour the daily hor d'ouvres set a pleasant tone for the trip.

Now it was time to see how all this preparation paid off. The brains behind this adventure were Neil and Lacey. They were in catarafts, as was another member of the expedition Steve, but his cataraft was a bit smaller. My friend John was with us in an IK (inflatable kayak). Neil and Lacey had made the trip before from a tributary that we would see in a couple of days. So for them the only thing new was a little stretch of river. Everything for my was new. One of the coolest things was that you could make seven kilometers per hour exerting hardly any energy, unless they decided to eddy out. Then I had to paddle like hell to get to a point where there was slack current. Usually I paddled too hard and overshot the mark, and got in the upstream eddy too soon, and ended up expended ten times the energy required for such a simple maneuver. Such was the case at our first camp. I barely had enough strength after beaching to offload my share of stuff. Food, kitchen pots and pans, cans, stove and fuel, more food, and a table. We really had remarkable little gear for a ten day trip. But we had tequila, and happy hour the daily hor d'ouvres set a pleasant tone for the trip.

Neil and Lacey live for this stuff. They would have done the trip without anyone else, but it was a unique opportunity for me when they opened it up to outsiders. Steve from Salt Lake has a lot of experience on rivers and oceans, and wasn't afraid of Mexico, and it seems who isn't these days. I feel safer there than my local Safeway, but that's another story. My friend John from Benson, AZ, had joined at the last moment. Now that he's semi-retired, short notice is plenty of time to plan a three week trip. I had just started a new job, and lest they think I could complete 3 months probation in three months, I had better sign up for unpaid leave. We passed the Jimador and smoked oysters and crackers and got a feel for what lay ahead.

The first major challenge to our expedition occurred the following morning. The water was up as we got underway. At a left bend in the river, the main current took a wide arc to the right and then a sharp bend to the left at a roiling four foot drop. We eddied out to scout on the left. A minor part of the current was flowing over some exposed boulders in front of us well downstream of the noisy cascade, so we prudently chose the easy route. Lacey went through first, gracefully straddling a boulder or two in her cataraft as she navigated the best water. Smooth and easy. We followed suit without incident, but the run made a good photo op. Later we encountered the Rio Sirupa coming in from the right, turbulent and carrying about three times the flow of the Tutuaca. This is the confluence where the Rio Aros gets it name. We scouted a broad bench on the left for an early lunch and set the tarp up as storm clouds gathered. With high ground nearby, we watched as branches and debris floated by, but "floating" can't accurately describe the motion of the detritus. At a little constriction upstream, and with a river gradient of about 25 feet per mile, jettison is word that comes to mind. Although it didn't rain on us, heavy rain clouds loomed in the high Sierra Madre to the east, and lightning flashed throughout the night.

The Aros flows through sparsely settled country. We saw the odd ranch house roof here and there, a few livestock, and an occasional cornfield. As we entered the congestion of El Refugio and El Cable, Neil motioned us over to scout an upcoming class III rapid. I had been daydreaming and taking photos of a suspension bridge so I was well on the left side of the channel as everybody eddied out to the right. Fighting the fast current I paddled like hell, but a mid river rock broke my progress and I high-sided my kayak against it. I still had my paddle in my right hand, and I scampered up on the left pontoon, but the current held my paddle underwater. I slowly got my hand free and climbed up onto the rock to get my breath. The IK was wrapped so well that with all my force I couldn't pry up either end to make one side or the other pop off. Miraculously all my gear stayed lashed in. Eventually, it became obvious that I needed assistance. Neil paddled out and made the eddy behind the rock. We worked one side of the boat and then the other, but the current as too strong. Finally, with four lines attached around and through one end and pulling with all our might, we bounced the IK free. What a great way to spend the morning. It was time for lunch by the time we got back to shore. The others mentioned that the river level was rising. We had lunch and made the scout of an upcoming rapid (Slapper-III), and continued on an overgrown trail to scout a series of class III's just downstream. We couldn't get to a good position, but when we returned about 3 hours later, our lunch beach was underwater. By the next morning the river level had risen another foot, and come within six vertical inches of our camp. Word got out about the boating party camped downstream from town, and we entertained a parade of locals throughout the day. They mostly came to put on the PFD's and helmets and get their photos taken in the beached rafts. They mentioned a guy that has kayaked that section for the last few years, and remembered Rocky who came down almost 10 years prior. I think their photos were posted to Facebook before they left the beach. Finally after 2 nights, we got to leave the beach, too.  The next section of the Aros is a big loop as it flows south and then north. The Rio Mulatos enters at the southernmost point. Across the cordillera from Refugio is Natora, Sonora, merely a 5 hour horseback ride away. This section has a number of rapids as it enters a gorge. John and I in the kayaks prudently held back watching Neil and Lacey's approach into the rapids, and everything went fine. Normally they would just hover above a rapid reading the line before the run. Sometimes they would stand up to get a view. Sometimes we had to eddy out to scout. Just when we were congratulating ourselves on our prowess, we eddied left to check out Olas Grandes, which turned out to be a sustained section of raging class III. It was decided to portage the kayaks, and the catarafts would skirt the bank. At the next scout, we studied the line and by following smooth water and avoiding one big hole on the right and one little hole on the left, "whoop", we would be out. Neil's words. Easier said than done, right? Well, it was just that easy in practice, too. Yeah!!

The next section of the Aros is a big loop as it flows south and then north. The Rio Mulatos enters at the southernmost point. Across the cordillera from Refugio is Natora, Sonora, merely a 5 hour horseback ride away. This section has a number of rapids as it enters a gorge. John and I in the kayaks prudently held back watching Neil and Lacey's approach into the rapids, and everything went fine. Normally they would just hover above a rapid reading the line before the run. Sometimes they would stand up to get a view. Sometimes we had to eddy out to scout. Just when we were congratulating ourselves on our prowess, we eddied left to check out Olas Grandes, which turned out to be a sustained section of raging class III. It was decided to portage the kayaks, and the catarafts would skirt the bank. At the next scout, we studied the line and by following smooth water and avoiding one big hole on the right and one little hole on the left, "whoop", we would be out. Neil's words. Easier said than done, right? Well, it was just that easy in practice, too. Yeah!!

We eddied out again past the Mulatos for another rapid. The Mulatos entered with low flow and mildly muddy water, and from here on out, it was no longer tierra incognito for Neil and Lacey. There were plenty of challenges like wave trains, whirlpools, and hydraulics from protruding rocks with deceivingly innocent holes behind them. My kayak had thigh straps for stability, and some additionally have foot braces. I had gear in front to brace my feet, so when I got to a particularly gnarly stretch of water, I would brace my feet and put my knees together. It just so happened that in a raucous wave train, I only had my left foot braced so I slipped my right knee free as I rode the waves and got ejected from the boat in slow motion. The current took me under for a while, and just as I thought that I wasn't going to get back up, I got a breath, but then I got pulled under again. Just before I got sucked back down I took a look around, and saw my boat about 20 feet upstream. When I came up the second time, I got tapped on the back of my helmet by the boat, so I grabbed a strap but I was too weak to flip the IK or climb aboard. By then Neil was there reminding me that I didn't have all day to dally. I climbed on, and eddied out, and got my breath- after a long, long time. The second time I flipped, that same day, I know that I braced and then put my knees together. If only I had practiced birth control kayaking and just put my knees together, I would have been fine. But no, I braced, slipped out of the thigh straps and went swimming again. Luckily, John was nearby and I grabbed his tether as he paddled past. Just then he had to maneuver through some rocks, and yelled "let go." I felt the bottom with my feet and I was about to let go, when I released the tension on has strap and rode the wave. I didn't have the strength for another ordeal like the last one, and I found that I could float with him like a sea anchor. The exciting section was over quickly, and he eddied out with me still in tow. John had flipped the second day out, but hadn't even let go of the boat, so as it turned out I was getting way more swim calls than anybody else.

The next day we put in to Natora. I don't know that we particularly needed anything, but if they had ice cold beer, a beer for second breakfast wouldn't be out of the question. We also wanted to call our shuttle driver and tell him we might be a day late. The call was super easy, and a bargain with 3 minutes for only 13 pesos. As we were making the second paseo of the town, after having passed the only tienda on the first round, a guy hailed us from his fancy truck. He had ice and cold sodas--no beer--and was picking up a guy from Rocky's group. What a small world. There are probably less than a dozen folks rafting that river in a year, and two groups show up in little backwater Natora on the same day. Well, the tienda didn't have ice, or electricity, so we got back on the river. An animated old woman followed us down to the boats determined to give us a dozen tortillas. It turns out that by giving us something that we accepted, she could now demand from each of us that we give her a gift. Savvy woman. All the rafting groups and shuttle drivers speak of her, so we weren't as special as she led us to believe.

The next day we put in to Natora. I don't know that we particularly needed anything, but if they had ice cold beer, a beer for second breakfast wouldn't be out of the question. We also wanted to call our shuttle driver and tell him we might be a day late. The call was super easy, and a bargain with 3 minutes for only 13 pesos. As we were making the second paseo of the town, after having passed the only tienda on the first round, a guy hailed us from his fancy truck. He had ice and cold sodas--no beer--and was picking up a guy from Rocky's group. What a small world. There are probably less than a dozen folks rafting that river in a year, and two groups show up in little backwater Natora on the same day. Well, the tienda didn't have ice, or electricity, so we got back on the river. An animated old woman followed us down to the boats determined to give us a dozen tortillas. It turns out that by giving us something that we accepted, she could now demand from each of us that we give her a gift. Savvy woman. All the rafting groups and shuttle drivers speak of her, so we weren't as special as she led us to believe.

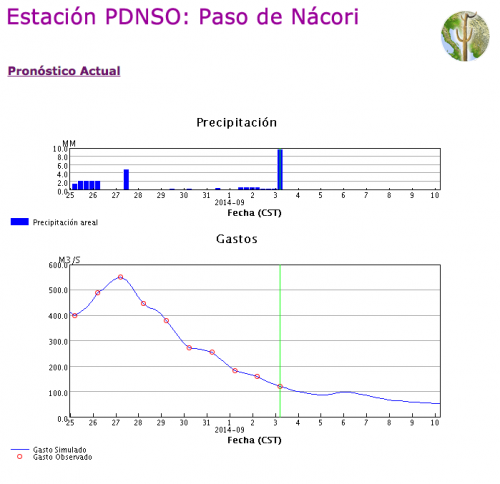

This section of river has some cool side trips like the slot canyons of El Aliso and Santa Rosa. The Aliso slot is a short section of smooth walls barely five feet wide. Steve's cataraft only made it in by the feel of it's whiskers. A hundred yards or so, and there's a little waterfall, but much past there is the debilitating sun saps your energy. Much of the land on the left side of the river from the gauging station at Paso Nacori is home to the Reserve where there is a protected breeding population of jaguar. These strong swimmers have been known to venture as far as Arizona where they have been sighted repeatedly in recent years. The gauging station as reading 1.9 meters when we were there- roughly 7000 cfs. The week prior, while we were at El Refugio, the reading was more like 19,500 cfs. Big water in anybody's book. The heat on the slowed down river on the more gently gradient was taking a toll. We stopped for a long lunch at a shady bench. As a troop of coatimundi showed unusual bravery at one end of the beach, a second party of rafters beached at the other end. This was Rocky's group that had put in on the Mulatos River. We leapfrogged with them for the remainder of the trip, and it gave us an opportunity to get more candid photos like in the rapids at La Morita (IV).

A smooth clear stream was entering from the right. The confluence of the Bavispe River and the Aros is the upper Yaqui River that flows into the reservoir Novillo. The river at this point is generally smooth and wide. The current isn't strong enough to justify the time in the hot sun, so we paddled, and played, and slipped into the river to cool off. By now the cliffs were diminishing, and the land was opening up. There was more livestock and signs of people. Just around the bend was another bridge. The take out was just upstream of the second bridge that we passed in 12 days and 220 river kilometers, and what an awesome trip it had been.